A glimpse into the future at Freight Gallery

Chris Combs and Ceci Cole McInturff presented SYLVAN, see their current show at VisArts

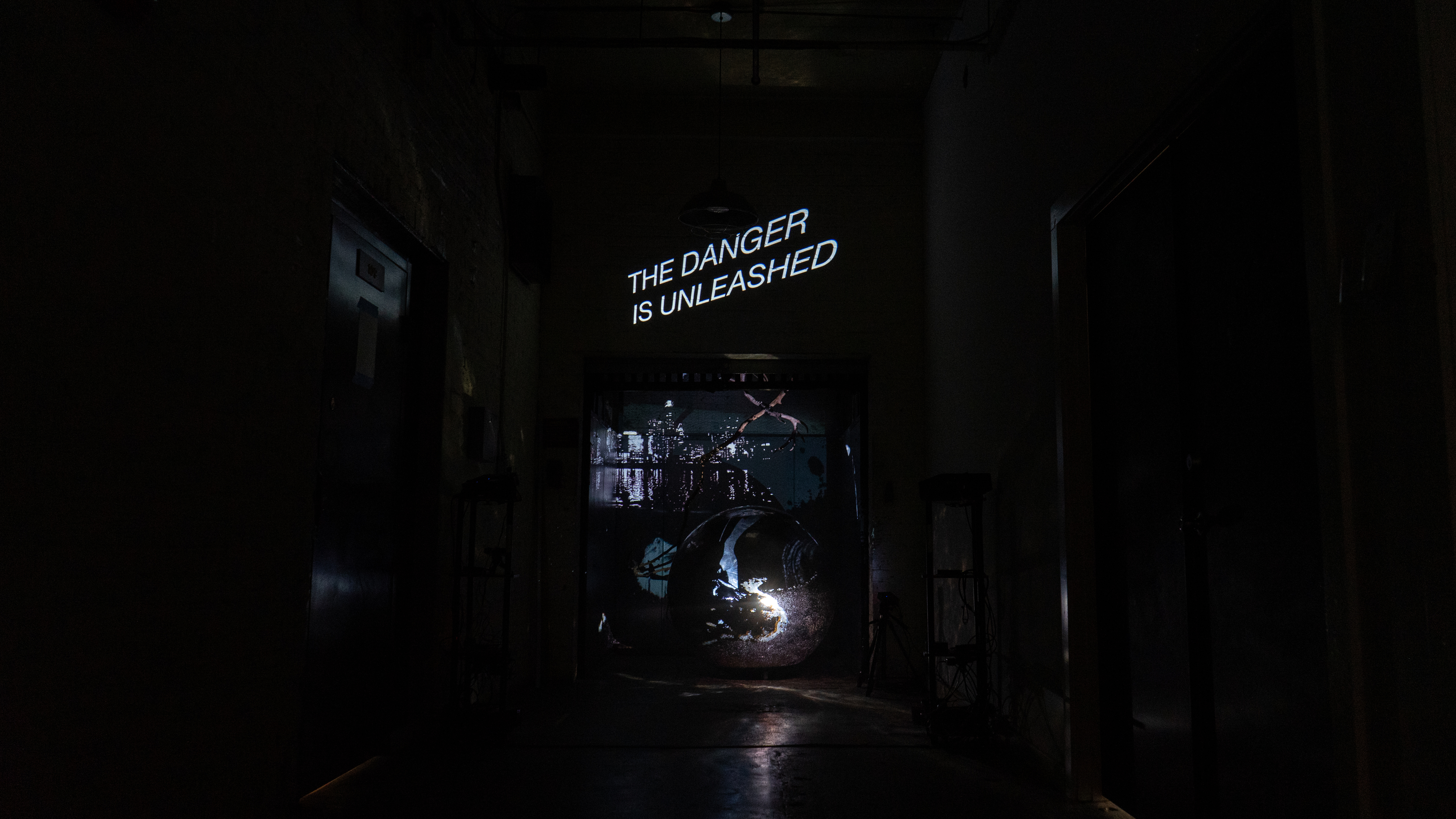

A black and white city skyline shimmers ahead while a water shore emerges and recedes on the gray cement floor. Light bounces off a massive spherical, reflective form casting moving light and shadows on the walls.

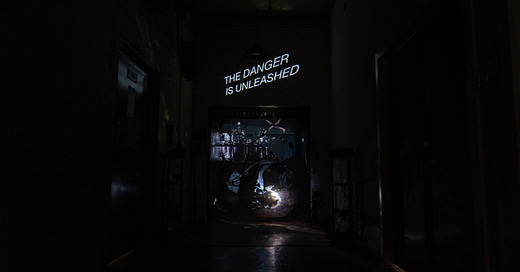

In Freight Gallery, a compact vignette leaks out across the walls, floor, and ceiling. The dark hall leading to the freight elevator-turned-gallery was only illuminated by overlapping projections depicting water bodies, flame-like forms, a city skyline, and above the freight door a harrowing message, projected line by line. Look carefully and hooves emerge. Not projected. Actual hooves illuminated by rippling water. Following the hooves up reveals a body made of a natural wood, thin, gnarled, and obscured by darkness. Keep looking and truncated wings suspend the creature above the metallic orb.

The installation SYLVAN, a collaborative work by Chris Combs and Ceci Cole McInturff, was shown at Freight Gallery on March 30.

The message projected above the industrial elevator was published in a 1993 report by Sandia National Laboratories titled, Expert Judgment on Markers to Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant. The plant, WIPP, is located in southeastern New Mexico and is designed to demonstrate the safe disposal of radioactive waste generated by the United States Department of Energy (DOE) defense programs.

The report details methods of communication, visual, auditory, architecturally, to warn future humans about the radioactive site. The proposed means of communication invoke retro-futuristic imaginings, but these aren’t pulled off the shelf at the local library; they are carefully determined texts and proposed constructions meant to reach future beings that encounter our heinous, devouring waste. One of those messages, generated in multiple languages at multiple levels of complexity, is the Sandia Message. As viewers stood at the projected shore, receding in the gaping mouth of the elevator, this message flashed above their heads.

The Sandia Message, formatted in poetic stanzas:

This place is a message...

and part of a system of messages...

pay attention to it!

Sending this message was important to us.

We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

This place is not a place of honor...

no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here...

nothing valued is here.

What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us.

This message is a warning about danger.

The danger is in a particular location...

it increases towards a center...

the center of danger is here...

of a particular size and shape, and below us.

The danger is still present, in your time, as it was in ours.

The danger is to the body, and it can kill.

The form of the danger is an emanation of energy.

The danger is unleashed only if you substantially disturb this place physically.

This place is best shunned

and left uninhabited.

Within the elevator, a being from the future hovers above the metallic core as images of what was, or would have been, undulate. This message, determined to protect the inconceivable future, was rendered startlingly before viewers, transporting them thousands of years into the future.

The experience of the installation prompts: How do you communicate the possibility of extreme suffering in a language, image, or infrastructure that is yet to be imagined, much less invented? What am I doing now that is impacting you, being of the future?

As we continue to navigate changes in technology, and with it increasing convenience and decreasing privacy, powered by water-cooled data centers, it’s not hard to connect the ramifications. While researchers have been sounding the alarms, metro posters advertise retro-style postcards depicting a Ferris wheel on the moon for crypto exchange while Harry Weese’s “classical vision of the future” arches overhead.

Suddenly, I’m like Dr. Manhattan who experienced the total of his life at the same time, all the time.

I’m standing in front of the freight elevator with a being of the future while weeks later I’m in the metro taking a photo of an ad, and a week before I’m visiting Chris Combs’ studio at Otis Street Arts Project.

His studio brims with tools and materials on tightly packed shelves. The walls carry mechanical finished pieces that light and blink. In the center of the studio was a work in progress, now installed at VisArts, the next iteration of the installation at Freight Gallery. Suspended is the massive metallic ball that anchored the vignette in the elevator. A mimic of it rests below, still being formed.

Combs says that the metallic anchor of the Freight installation is in some ways referencing the “demon core,” a plutonium sphere manufactured by the Manhattan Project. The core saw two torturous, fatal radiation accidents and was eventually melted down to be recycled for use in other weapons.

Despite nuclear impetus, the installation isn’t meant to warn viewers of the danger of literal radiation, but acts as a metaphor for the potential cost of technology.

“I was thinking about how social media was kind of like radiation. When you're experiencing radiation, it actually kind of warms you up a little bit. It feels good,” said Combs.

He brought up the Revigator, which used the power of radioactive-infused water to supposedly “remove cellular poisons.” Similarly, apps that are supposedly designed to connect us spark dopamine hits, creating addictive impulses. While scrolling Instagram won’t cause your jaw to crumble in the hands of your dentist, like one of the Radium girls experienced, it can change your brain, radically decrease your privacy, and impact your ideologies and civic engagement.

While I’m in Combs’ studio, I’m also scoffing at the Whole Foods self-checkout because an automated voice reminded me to use the Amazon-powered palm scan. As I walk out I unlock my phone using face ID.

Combs continues, explaining that social media was just one example, and more generally, interactions with advancing technology need to be questioned and carefully navigated.

He said a goal of his artistic practice is to point out ways that the world has changed. By creating interactive, tech-integrated objects, Combs asks viewers, “How does this change the way that you interact with the world?”

Knowingly or not, our habits are continually impacted and tracked by apps and algorithms. Apps meant to keep us informed or ones that harness the power of a streak are really designed to keep us hooked.

Another example is the forced integration of “AI” into every website. This surge in integration and resulting use is now being used to justify bringing Three Mile Island back online, Combs tells me, backed by Microsoft to power data centers, including AI technologies.

I’m baffled when a person I am dating tells me he fed images of me into an AI generator to merge my likeness with a character from his favorite show. I worry about how my image will now be used to generate, train, and create images of me, or parts and pixels of me, doing… anything.

Combs continues, “The idea of like failed nuclear power plants being brought back online and operated commercially by a company that does not necessarily value anything beyond value to its shareholders… that's cursed.”

And, he notes, AI, as it’s marketed, doesn’t exist.

“There is no artificial intelligence. There is no AGI, as the AI people call it. No general intelligence. There's no reasoning. There's no logic,” he says.

When you combine the environmental impact of water-cooled, newly nuclear-powered data centers with habit-forming technologies that shape how we think, interact with each other and our world, then a comparison to skin dissolving radioactive exposure doesn’t seem like such a stretch. As a viewer of the installation and as a tech user, I was left to assess the known and unknown consequences of my decisions.

Combs says it is important that the experience of the artwork offers room for the viewer to consider their own relationship with tech. While one look at the installation won’t make someone reject social media for eternity, he said, it can nudge them to question.

Standing in Combs’ studio, I ask, “ How is our care being disrupted by the systems that we're participating in, by convenience?”

Combs continues the line of questioning, “and to whom do we have responsibility for these actions that we take?”

He continues, “ I think that I am approaching all of this from this perspective of deep caring. I want to invoke problems so that we can all fix them together.”

The teams of researchers who wrote the Sandia message determined that there are transcendental forms of communication that reach through culture and time, “forming a species-wide ‘natural language’ we are all either born knowing or learn from the early life experiences that are common to human existence everywhere” (p. F-39).

The writing continues:

There are particular places (built-forms and natural and made-landscapes) that elicit powerful feelings in almost everybody. These places feel "charged," almost in an electric sense, and the places seem filled with meaning. Most places, of course, are not charged and few are filled with meaning. The places that do carry charge and meaning are sometimes beautiful, but at least as many are ugly, awesome, or forbidding. Their importance is in their content (the message), far more than their form, and the success of their forms is in their expressive capacity, not their aesthetics.

In her studio at Otis Street Arts Project, Ceci Cole McInturff delicately and precisely combines organic forms, the skill of which is so practiced that it is only by the impossibility of the material combinations that the transformation can be identified. Carefully wrapped wire attaches but blends. Bound furs lose connection to their bodily form and become webs or hives. This is her “natural language.”

Across the walls and hanging from the ceiling are forms that are ugly, awesome, forbidding, and sometimes unidentifiable - all are charged. Curly sheep’s wool is draped over a chair. Husks mounted on the wall take on the shape of skinned haunches or bustiers. Horse hair is rhythmically threaded and knotted through the edge of a massive palm husk that evokes a prehistoric seed pod. On her desk are stones with bird wings.

Combs explains it this way: she knows how to make disparate parts merge together to become something “exquisitely correct.”

She presents to me the excerpts from Leonard Koren’s Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets and Philosophers. It explains the qualities used to identify something as wabi-sabi, some of which are: acceptance of the inevitable, comfort with ambiguity, fundamental uncontrollability of nature, accommodates to degradation and attrition, corrosion and contamination make its expression richer, attention to the present, and comfort with ambiguity and contradiction.

I’m walking through the azalea collection at the National Arboretum to be reminded of home, while years earlier I’m in college, standing in the unpaved alley behind my grandparents’ house, taking photos with the overgrown azaleas that extend far past my crown. Their electric pink blooms make me squint in the piercing sunlight.

Cole McInturff leads me from one studio to another. This second is a warehouse. Her work is wrapped in plastic, stacked, and suspended from the high rafters. There are more husks. They are leathery with raised lines swooping over their curved forms. The husks are hard, surprisingly thick, and fold in on themselves. Some have gold painted on one side, some have hair that cascades, others have stitches bound by hand.

The forms are bodily, otherworldly, but unmistakably organic. There is something valuable, she told me, about feeling a sense of “weird familiarity” with these forms.

I’m in grad school, on all fours in messy art studio clothes, crawling under draped fabric while a student a year ahead of me takes reference photos for a painting. Years later, she posts online that she has an upcoming show, and one of the paintings that has my likeness is in it. I swipe through the photos, excited to recognize a part of me.

That sense of familiarity shared with all living things is seen in how Cole McInturff cares for the materials she works with and creates - delicately measuring what her impact should be and, once transformed, honoring them still as formerly living entities.

There is a sacredness, a preciousness to these materials because they were once alive, she says. Gnarled wood may usually be disregarded, but through Cole McInturff’s selection and attention, the material is honored. One such massive, stretching piece of wood is hanging to the side of the studio and attached at the end are fierce, sharp talons.

She explains, “To me, whatever I'm dealing with collaboratively, materially, I'm still saying pretty much these things: Broaden your view of beauty. Appreciate impermanence. And that we have something in common [with] anything living.”

For Cole McInturff, the materials themselves directly acknowledge impermanence and she shares that even she will not work with these materials, at this scale, forever. Her practice will change and evolve as the materials will, as the environment will. And this is not to be mourned, but accepted, as the concept of wabi-sabi suggests.

Again, time collapses, I’m mesmerized by the projected shore and flame reflected on the surface of the steel ball while I am, on an undestroyable level, a nameless, unidentifiable building block that becomes and becomes and becomes until I am a small, unperceivable part of a being of the future.

Cole McInturff continues, “ Everything is endlessly becoming something else.”

UNFORSEEN is on view at VisArts at Common Ground Gallery until July 20.

Join the opening celebration Friday, May 30, 7-9 PM. See the next show at Freight Gallery on June 1st.